The Lobbyists Are Loving Life

The Big Beautiful Bill Act was a love letter to the oil and gas industry. And now we're truly seeing the consequences.

Last Saturday, on a beautiful fall morning in Santa Fe, New Mexico, I attended an event on public lands featuring law professor John Leshy being interviewed by writer William duBuys. There are a lot of experts today on America's public lands, but few can rival the knowledge stored in the 81-year-old Leshy's noggin. Now an Emeritus Professor at the University of California College of the Law, Leshy previously served in the Interior Department in the Carter Administration, as special counsel to the Chair of the Committee on Natural Resources for the U.S. House of Representatives in the early 1990s, and as the Solicitor for the Interior Department during the Clinton Administration.

As if that wasn't qualifying enough: he also wrote the seminal book on the history of America's public lands, Our Common Ground, a sweeping, fascinating tour that begins back in the 1700s and brings us all the way up to the present day. (Side note: if you care about public lands, buy his book. Roughly 90 percent of what I now know about the topic is in there.)

The event drew a packed house, demonstrating the salience of public-lands issues at the moment. In fact, most of the audience members, including me, seemed to nod along with Leshy as he spoke, demonstrating our familiarity with the current threats to our common trust that he was carefully unpacking. But one thing Leshy said did surprise me, and I've been ruminating on it ever since. He was talking about Utah Senator Mike Lee's now-infamous proposal last summer to sell off millions of acres of public land—the one that galvanized millions of Americans and went over like a lead balloon.

"Some people—the real cynics," said Leshy, "think that Lee proposed his amendment to provide a smoke screen to allow the One Big Beautiful Bill Act to have some really terrible things for public lands in it—ones that didn’t get any attention because the attention was all gathered by Lee’s proposal."

I count myself as neither a cynic nor a conspiracy theorist. I believe Lee truly does want to sell our lands and will continue to attempt to do so—because he has stated both, repeatedly. But even if providing a smokescreen for nefarious activity wasn't his true motive, I have to admit it was still an incredibly effective one.

Remember, the Big Beautiful Bill was more than 1,000 pages drafted in a matter of weeks and without a single public hearing. Hardly anyone but a small group of insiders knew what was in it. And while conservationists and hunters and anglers and every other type of outdoor lover were still clinking glasses to celebrate the fact that Lee pulled his proposed land-sales amendment, there was a conspicuous lack of outrage drummed up for what actually did make it into the bill.

And what that was was a giant, unprecedented gift to extractive industries, almost certainly handwritten and bow-tied by those same recipients. The Big Beautiful Bill Act, explained Leshy, "commands the federal government to offer to lease for oil and gas millions and millions of acres of public lands over the next ten years. It's not an instruction to consider or entertain the possibility, it is an instruction to [provide], on a schedule, quarterly lease sales. Nothing like this has ever passed before."

Indeed, you can trace almost every recent piece of bad news around public lands to these directives in the Big Beautiful Bill—from the decision to rescind the Public Lands Rule, to the recent proposal to open up oil and gas drilling around iconic places like Chaco Canyon and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

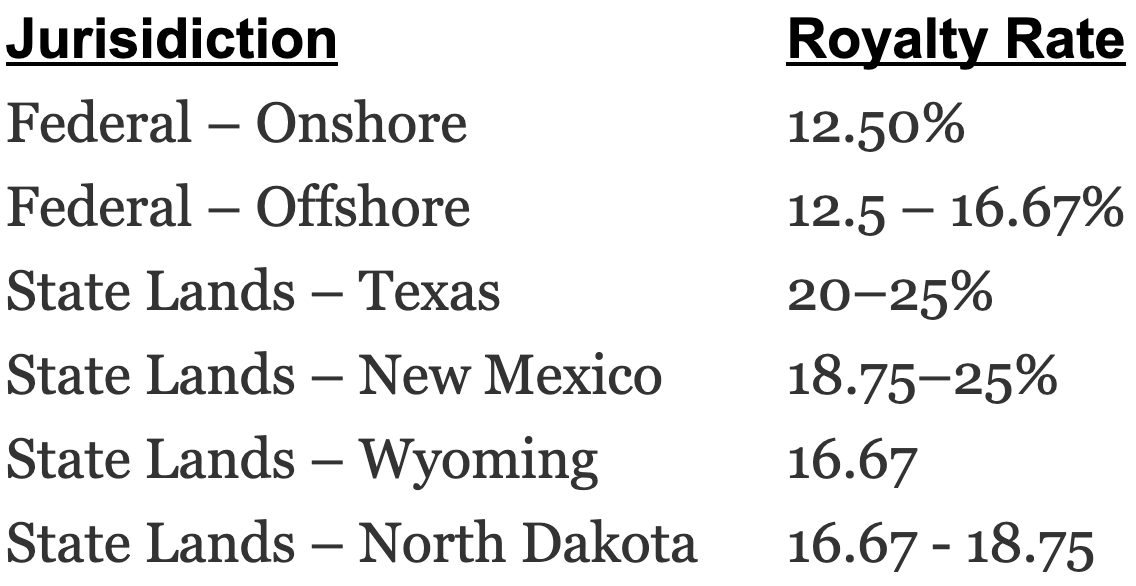

Here's what's even worse: we the American public—the owners of these lands—had no say in this new instruction, and we will be taking in far less than the market value of those seemingly endless new leases. Why? Because the BBB also reverts oil and gas royalty rates from 18.75 percent back to 12.5 percent. The rates were increased in 2022 for the first time in more than 100 years, and the BBB reversed course just three years later.

Think about that. As part of a massive tax-cut bill that nonpartisan scorekeepers estimate will add trillions of dollars to the deficit over the next decade, we decreased our ability to generate revenue from public lands that could offset the exploding deficit.

It is yet another example of the federal government still treating our public lands as a bargain that must be gifted to industry rather than a trust that must be protected—and monetized fairly—for the American people.

The change in royalty rates is particularly galling when you wind back the clock to January and listen to the sermon on fiscal responsibility that Interior Secretary Doug Burgum was preaching during his confirmation hearing. He explained that he viewed America’s public lands and waters as part of the country’s “balance sheet,” and that we needed to inventory the trillions of dollars worth of oil, gas and minerals waiting to be extracted beneath the surface.

“We have all this debt,” Burgum said. But “we never talk about the assets. And if we were a company, they would say, Wow, you're really restricting your balance sheet.... It’s our responsibility to get a return for the American people.”

Lowering the royalty is completely antithetical to this philosophy. It represents a massive subsidy for an industry that does not need one, and it means companies pay less of their production revenue to the federal government. Analysts focused specifically on fossil-fuel royalty changes estimate direct lost federal royalties of roughly $10 to $11 billion between now and 2035, when the bill is scheduled to sunset.

We have decades of debate in the public record to explain how we arrived here and why these royalties remained so low for so long. Federal agencies—and, perhaps more important, oil and gas industry lobbyists—have repeatedly argued that if royalty rates go up, companies will simply move to state or private lands. They'll abandon us!

But data and case studies show the opposite. Production on state lands in New Mexico, where I live, boomed after the state raised its rates to as high as 25 percent. The Permian Basin, which straddles federal, state, and private lands, has remained a top-producing region regardless of the rate differential. As a result, New Mexico has the one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, currently worth some $66 billion.

Contrast that with how we're managing this part of the "balance sheet" at the federal level. Government Accountability Office and Congressional Research Service reviews have consistently concluded that a modest royalty increase (from, say, 12.5 percent to 18.75 percent, as instituted under the previous administration) would barely affect drilling decisions, since factors like geology, infrastructure, and oil prices matter far more than small differences in royalty rates.

States like New Mexico and Texas have already demonstrated that the market will bear much higher rates. Even in North Dakota, Burgum's home state and the third largest oil and gas producer in the Lower 48, the industry continues to thrive despite paying much higher royalty rates than what the federal government demands. Yet Washington hasn’t adjusted to the new reality.

That lost revenue we receive from public land leases isn’t theoretical—it’s real money that could support local communities. Half of the royalties from federal lands go to the states. When federal royalty rates drop, state and local budgets suffer.

Wyoming, where the royalty rate on state lands is about 16.67 percent, offers a stark example of how bad the federal deal is. Researchers at Taxpayers for Common Sense estimate that over the past decade, Wyoming lost out on roughly $2 billion in additional royalties because oil and gas companies operating on federal lands in their state were charged the lower rate. Even a recent single lease sale flagged for Wyoming under the new lower rate in the Big Beautiful Bill is estimated to cost the state about $11 million over the lifetime of the wells.

When we let the federal government under-charge for drilling, we lock Americans into one narrow kind of land use and penalize the states and counties that host production. At the same time, we effectively ignore two of America’s fastest-growing economic engines: outdoor recreation and conservation. By privileging accelerated fossil-fuel leasing and slashed royalties, the Big Beautiful Bill says: “We value drilling over trails. We value rigs over recreation. We value short-term gains over long-term stewardship”

A few days after the Leshy event, I read a brand new report titled "Outdoor Recreation on Federal Public Lands & Waters: A Valuable American Asset." It was put out by the Outdoor Recreation Roundtable (ORR), and conducted by independent research firm Southwick Associates. (Full disclosure: a member of RE:PUBLIC's board works for ORR). The report illustrates the chronically overlooked value of our public lands to "America's balance sheet."

According to the report:

- Outdoor recreation generates $1.2 trillion in economic activity and supports 5 million jobs nationally.

- Outdoor recreation's contribution to the economy is larger than other well-known industries such as, well, oil and gas, mining, agriculture, utilities, and broadcasting/communications.

- Roughly $351 million is added to the U.S. economy every day from recreation on federal lands and waters, "the equivalent to hosting eight Super Bowls every month in economic impact."

I drive a car fueled by gasoline. Next Monday I am getting on a plane to California. I recognize that we have not yet made the full transition to clean energy and that oil and gas extraction will remain a part of our management plan for public lands for the foreseeable future.

But not the only part.

Imagine a world where our leaders in Washington looked for ways to subsidize the recreation economy and the longterm value of conservation to the same extent it supports the oil and gas industry.

This is the problem that public lands stewards face—on both sides of the aisle. It's the problem we all have to solve if we want to change this lopsided and shortsighted dynamic. Oil and gas producers have well-organized, well-funded lobbying operations at the federal level. The recreation industry and conservation groups have a disparate, fractured operation—and a fraction of the influence in Washington. And the potential beneficiaries of higher royalties and smarter stewardship—we the taxpayers and land owners—have no direct lobby at all.

Until we fix that, what we get is the Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Meet the Team

Elizabeth Hightower Allen, Editorial Director

It's been quite a fruitful free-agent signing period this fall over at RE:PUBLIC. We recently inked a deal with one of the best editing minds in the business. Elizabeth was the features editor at Outside magazine for more than twenty years, and has recently been editing award-winning nonfiction books, including First and Wildest, published on the centennial of America's first wilderness area, the Gila. She helped oversee our first batch of longform stories published in October, and I can't wait to share some of the latest stories and amazing voices she has in the pipeline.

Favorite public land: White River national Forest, Colorado

Why did you join RE:PUBLIC? Like just about everybody, I feel grounded in something bigger on public lands—a sense of awe and a connection to something sacred. It's not just the land itself—it's our ongoing decision to hold these lands in common. My career as an editor covering the environment and adventure has been an expression of that gratitude.

What part of RE:PUBLIC's mission resonates most with you? It's nonpartisan. All of us who spend time on public lands—hunters, fishers, ranchers, paddlers, campers—can agree that these places are worth safeguarding.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Every Friday, our team shares critical stories about public lands from around the internet. This list could be exhaustive and exhausting, but our intent is to inform, not overwhelm. Instead, we choose three to five important stories you should be aware of—including at least one piece of good news.

The Good: Colorado State Land Board approves La Jara Basin sale "An army of heavyweights descended on the board’s five commissioners in recent days, leaning on them to follow through with a plan in the works for nine years to sell the La Jara Basin to the federal government. The pressure followed recent revelations that the board was considering canceling the deal and walking away from more than $43.5 million in federal conservation funding allocated over the last three years. 'This project is essential to the San Luis Valley, to Colorado and to the nation,' Ken Salazar, the former secretary of the Interior Department, U.S. senator and Colorado attorney general to Colorado, said in an interview with The Colorado Sun."

Additional context here:

The Bad: Trump’s DOE may soon force more coal plants to stay open"The Trump administration appears poised to force more coal plants to stay open past their planned closing dates — an unprecedented intervention in the power sector that is already making energy even more expensive for Americans. The first signal of the strategy came in late May. A week before the J.H. Campbell coal plant’s scheduled shutdown, the Department of Energy directed the 63-year-old facility in Michigan to keep operating for 90 days. The agency has since re-upped that order, and the power plant’s owner, Consumers Energy, expects another extension later this month. Through the end of September, the move had already cost Consumers’ customers a total of $80 million, or roughly $615,000 per day.

The Ugly: Trump administration planning to allow oil and gas drilling off California coast "The Trump administration is planning to allow oil and gas drilling off the California coast for the first time in decades, according to a draft plan shared with the Washington Post. The move is guaranteed to set up a battle with the state’s governor, Gavin Newsom, a staunch opponent of offshore drilling.The plan would include six offshore lease sales between 2027 and 2030 along the California coast, as well as the expansion of drilling into the eastern Gulf of Mexico, which Donald Trump renamed the Gulf of America. Drilling has typically been avoided in the area due to fears from Florida Democrats and Republicans around beach pollution and an overall negative impact on tourism."