Father Knew Best

Amidst all the threats to public lands, now is a moment to remember the ‘why’—to touch the root of our passion for these places. My father was that root for me.

When I was going into first grade, my family spent the summer driving from our home in Boston, Massachusetts, to Pacific Grove, California, where my father was scheduled to do a year-long teaching exchange at a boarding school. We took a meandering path across the country, a route that disregarded speed in service of our biggest priority: visiting as many national parks in seven weeks as a family of four in a beat-up station wagon could endure.

How my parents pulled this off is still a mystery to me. This was before the internet; before you could research and pre-plan a trip to within an inch of its life; before handheld screens sanded away the rough edges of boredom on interminably long drives; before you needed reservations six months in advance to see Old Faithful; before GPS told you exactly where to go. On those rare occasions when we stayed in air-conditioned Motel 6’s and not at KOA's in our steamy 100-pound, four-person tent, I remember my parents unfolding a paper map as big as a table cloth over one of the two queen beds, tracing various routes with their fingers, circling parks in ballpoint pen.

What makes that trip even more remarkable is that my parents didn't grow up camping or with any real outdoor role models. My mom, at least, grew up skiing, but my dad was strictly a ball-sports kid growing up in Connecticut. He wasn't raised on trail mix and sleeping bags, and the only time he’d spent in a tent was when he was in the army. For him and my mom to pull off this expedition—two months on the road with two young kids, tents to pitch, camp stoves to master, meals to plan, unpredictable weather to contend with—was an enormous undertaking. My dad was basically our Clark Griswold, right down to the Ford Fairmont station wagon, three years before National Lampoon's Vacation made cross-country family road trips iconic.

Looking back, that whole adventure seemed to be an unintended celebration of the rare freedom we Americans have to roam. At night, my parents even took turns reading out loud to us A Walk Across America, a bestseller by a man who—you guessed it—takes it upon himself to walk across the country, unencumbered by society’s normal rules and expectations.

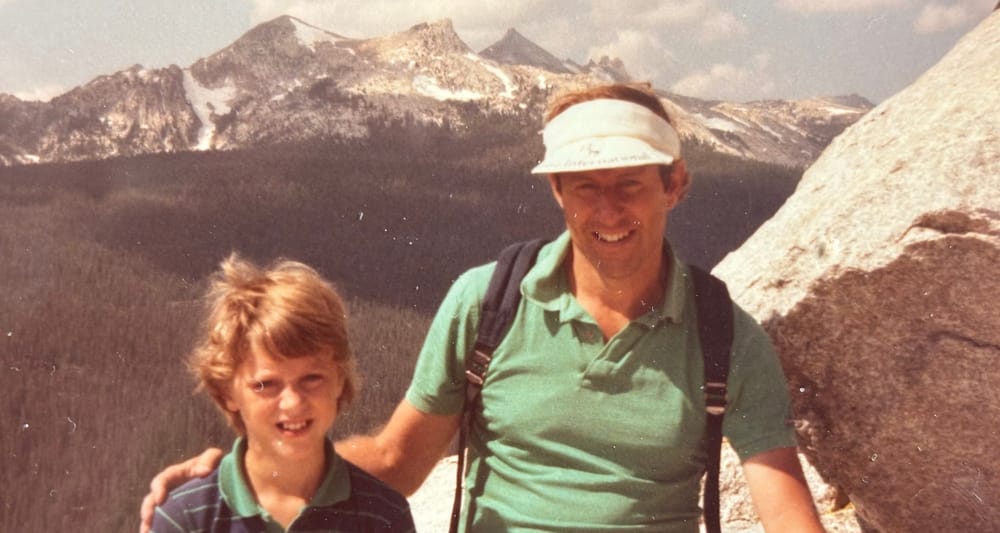

I was only six, but some of the memories from that first trip are still vivid 45 years later. There was the time we took a guided tour into Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, and I was terrified when the ranger asked us all to turn off our flashlights so we could experience the true darkness. That time my sister and I hid under blankets in the back seat, as my father drove the harrowing, guard-rail-free Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. The hike with just my dad to the top of a peak in Yosemite—a hike I never wanted to end because of how much I craved his one-on-one attention. And driving for hours in Yellowstone looking for grizzly bears, something my dad, in a grand miscalculation, had promised us for 2,000 miles that we were guaranteed to see.

The family memory that really sticks, however, was in the Grand Canyon. One night, as we watched the sun set on the North Rim, my dad got a wild hair. As the last light faded from a scene of impossible scale and color, my parents tucked my sister and me into our “mummy bags” in the back of the station wagon. We then embarked on a ridiculous, all-night drive to catch the sunrise on the South Rim. My sister and I slept soundly, suspended between the two great halves of the trip, unaware of the sheer commitment required. When we awoke, our minds were blown by the view outside the back window.

My father died in May of this year, just as I was completing the business plan for RE:PUBLIC. He passed away quietly, laying in a bed in the memory care unit of his group home, overlooked by my mother, his wife of 57 years. He left behind a silence that still lingers, that changes the shape of everything.

Grief is a deeply private experience, but perhaps the secret to healing is making it public. And for me, this particular loss feels connected, in a fundamental way, to the mission we share at RE:PUBLIC. Amidst the daily churn of relentless legislative threats to public lands and the difficult headlines currently emerging from this administration, it is easy to become overwhelmed, to let cynicism settle in. For the last ten weeks, I’ve written a lot about policy. Bad, infuriating policy. But I’m not going to write about threats to our public lands and waters this week. Right now is a moment, I think, to quiet the noise and remember the ‘why’—to touch the root of the passion, the personal reverence for the land, that brought us all here. It's rediscovering that collective reverence that will get us out of this mess.

My father was that root for me. He was not a hunter, a fisherman, or an avid outdoorsman in the traditional sense, but he was a man who understood the profound value of exposure and discovery. And over the past few months, I’ve realized that so much of what I care about—public lands, open space, the right to roam—started with a handful of bold, unlikely decisions he made long before I understood their importance.

The first was before I was born, when he made the unconventional choice to quit the world of corporate banking in New York City to become a high school teacher. That changed the entire arc of my childhood. It meant that instead of being raised in an apartment in the city, I lived as a “faculty brat” on the campus of the Noble and Greenough School in Massachusetts, where he taught. For me, that campus was basically a 187-acre passport to freedom. I wandered the woods and fields with friends for hours, completely unsupervised, exploring trails, flipping over logs, climbing trees, skating on frozen ponds. I didn’t know it then, but I was learning how to be outside—how to feel at home in a landscape.

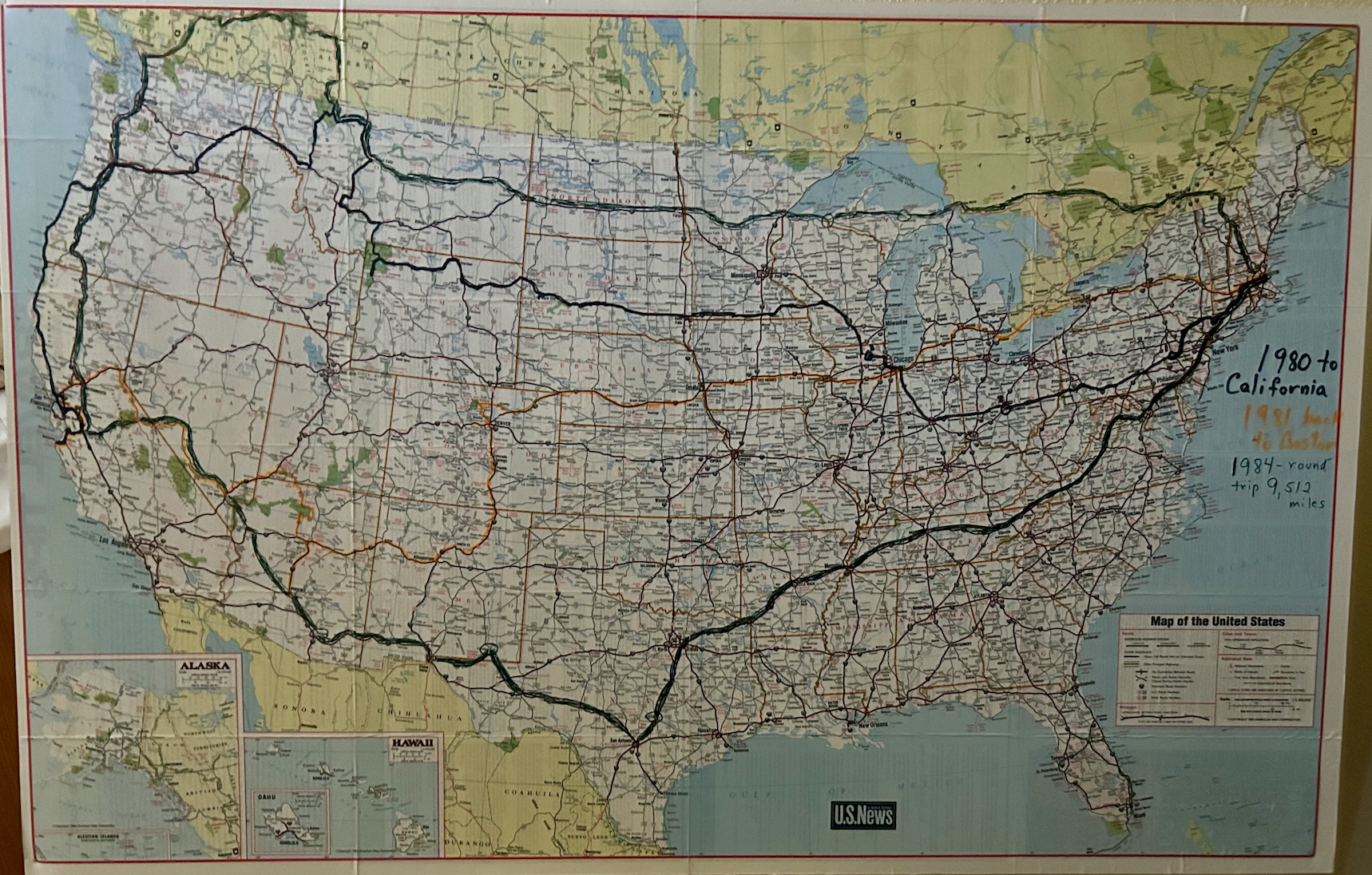

The second decision was moving to California for a year. That required summer trip wasn‘t the final adventure—it created a new tradition. We repeated the meandering journey on the way back to Boston the following summer. Three years later we did it again—driving more than 9,000 miles from Boston to Monterrey, up the West Coast and over to the great parks of Canada, and back across the Midwest. There are too many memories from those trips to share in this space, but the common theme was misadventure. It was on that last trip that I learned that when things go wrong—the campground is full, a wrong turn is taken on a hike, it snows in July—well, that’s when the true magic happens. My dad didn’t court misadventure, but he had a gift for finding it.

The last big decision came a few years later, when he packed us up and moved the family across the country to Portland, Oregon, where he took a job as the head of a high school. By bringing us West, he put me in the path of the places that would shape the rest of my life. Suddenly I had access to the outdoors on a much grander scale—and the outdoor sports I still love today. A seventh grade teacher took me on my first backpacking trip, a seven-day romp through the Goat Rocks Wilderness. (Hi Robin, I hope you’re reading this!) A high school teacher taught me the basics of mountaineering, then led me to the top of Mount Hood.

My dad remained a spectator to these pursuits. He didn't teach me how to tie a fly or read a compass or self arrest on a glacier, but he showed me the humbling, non-negotiable scale of the public lands that belonged to all of us. He opened the book, and let the wilderness write the first chapters of my life.

I’m certain that everyone reading this, every advocate, journalist, rancher, scientist, ranger, or citizen who shows up for public lands started with moments like mine. Someone quit a job. Someone moved the family somewhere new. Someone drove for hours to get to a trail. Someone put a rod in a child's hand. Someone said, Look at this. Isn’t it extraordinary? If we’re going to reach the people who can protect our lands for the long run, we need to celebrate those moments. We need to rediscover the reverence for land, not just focus on the battles.

Around the time of the Covid pandemic, we confirmed as a family what we had long suspected and tried nonetheless to deny: my dad had dementia. We never got an official diagnosis, but by then all the classic signs had created a mosaic with an irrefutable image. The man with the flawless sense of direction was suddenly disoriented on drives to the grocery store. His favorite jigsaw puzzles would sit for months uncompleted. His stories would increasingly peter out when he couldn’t grasp the words he wanted to say to unspool the narrative.

Dementia is a cruel and confounding disease. Anyone who has experienced a family member who has it knows that “the long goodbye” is the most apt description. It’s not only goodbye to a loved one, but goodbye to many shared memories that bind you together—only, you never really know which memories will fade and which will get locked down. For my dad, even up to the end, the trips across the country somehow never faded.

On one visit back home to Portland, after I unpacked and got settled, my dad pulled me aside and told me he wanted to show me something. This was about two years before we had to put him in a memory-care center. We walked into their den, and he pointed to the bookcase. At the top, was a large map of the U.S. on foamcore poster board, leaning against the wall like a school science fair presentation. And on that map, my dad had traced the routes of all three of our cross country trips. He never said it, but I knew his intention. He wanted to make sure we all remembered.

When the news gets overwhelming these days, when the setbacks pile up, I try to remember my father unfolding those maps, planning routes to places he'd never seen, learning to do something he'd never done because he believed we should see them, too.

These lands will outlast administrations. They will outlast us. But the choice to protect them, to keep them public, to ensure that other families can have their own three summers of discovery—that choice is ours to make, again and again, for as long as it takes.

Underneath all of the work we want to do at RE:PUBLIC—under the reporting, the watchdogging, the policy fights—is love. And I don’t mean that in a soft or sentimental way. I mean love in the foundational sense: something that calls you to protect what shaped you. That’s why this work matters. Not just to resist what’s being lost, but to protect the places that quietly make us who we are—and the places where the next generation will grow into themselves, too.

The fight for public lands is, at its heart, a fight to preserve the opportunity for every American to find their own path to reverence, just as my father allowed me to find mine.

Meet the Team

Jonathan Dorn, Board Chair

When we'd raised enough money at RE:PUBLIC to graduate from the initial start-up phase, I was able to start working full time as an employee of the organization—which also meant giving up my position as leader of the board of directors. It was a strange feeling to suddenly give up that control, but any concerns I had were immediately assuaged by the election of Jonathan Dorn as our new chair. I've known Jon for more nearly two decades—initially as a competitor when he was the editor in chief of Backpacker magazine, and later as a colleague and manager, when he oversaw me and my team at Outside after it was acquired by the newly formed Outside Inc. in 2021. He's the smartest strategic thinker I've worked with in media, and I'm thrilled to have him on board to help plot the future of RE:PUBLIC.

Favorite public land: The next one—it's the place I haven't visited that may hold some unforgettable new experience or vista.

Why did you join RE:PUBLIC? Serious reporting of the sort that Chris is so well-prepared to oversee has never been more critical to the preservation of our nation's wild spaces and biodiversity. From urban oases to iconic national parks, America's public lands enrich the lives of tens of millions of citizens every day, conveying physical and mental benefits that countless studies have illuminated. I've devoted my career to journalism that inspires and enables people from all walks of life to get outside and enjoy nature, and RE:PUBLIC is a natural extension of that work. I love the idea that our storytelling will drive home the importance of protecting our contry's natural treasures for future generations.

What to public lands mean to you? A simple, magical, and prescient idea that is unique in all the world and critical to the health of our communities, country, and planet—and a gift we must unite to pass along to our children and grandchildren.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Every Friday, our team shares critical stories about public lands from around the internet. This list could be exhaustive and exhausting, but our intent is to inform, not overwhelm. Instead, we choose three to five important stories you should be aware of—including at least one piece of good news.

The Good: Bipartisan Public Lands Caucus Endorses Public Lands in Public Hands Act "The Bipartisan Public Lands Caucus, co-chaired by U.S. Representative Gabe Vasquez (D-NM), U.S. Representative Ryan Zinke (R-MT), U.S. Representative Debbie Dingell (D-MI), and U.S. Representative Mike Simpson (R-ID), announced its official endorsement of the bipartisan Public Lands in Public Hands Act to safeguard America’s public lands and ensure they remain open and accessible for all. This is the first bill endorsed by the Bipartisan Public Lands Caucus, which was founded by Rep. Vasquez and Rep. Zinke in May 2025."

The Bad: Trump Moves to Weaken the Endangered Species Act "The Trump administration proposed on Wednesday to significantly limit protections under the Endangered Species Act, the bedrock environmental law intended to prevent animal and plant extinctions. Taken together, four proposed new rules could clear the way for more oil drilling, logging and mining in critical habitats for endangered species across the country. One of the most contentious proposals would allow the government to assess economic factors, such as lost revenue from a ban on oil drilling near critical habitat, before deciding whether to list a species as endangered. The Endangered Species Act requires the government to consider only the best available science when making these decisions."

The Ugly: Administration's plan waives protection at more than 80 percent of wetlands "The Trump administration has proposed dramatic new standards under the Clean Water Act that would leave scores of wetlands and small streams more vulnerable to pollution. Just 19 percent of wetlands by acreage—about 17,360,970 acres—in the contiguous U.S that have been mapped by the federal government would be protected under the sweeping draft “waters of the U.S.” definition unveiled Monday. That’s according to an estimate in a regulatory impact analysis conducted by EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers and released alongside the proposed rule. Trump administration officials said the proposal conforms with Sackett v. EPA, a 2023 Supreme Court ruling that asserted that only wetlands that directly touched a relatively permanent waterway – like a river or lake – fell under the scope of the Clean Water Act and the regulatory powers of the federal government."