The Feculent Bucket of the Culture War

When public lands become political symbols like everything else, it puts America's last bipartisan political cause at risk.

“So, why a news organization dedicated just to covering public lands?”

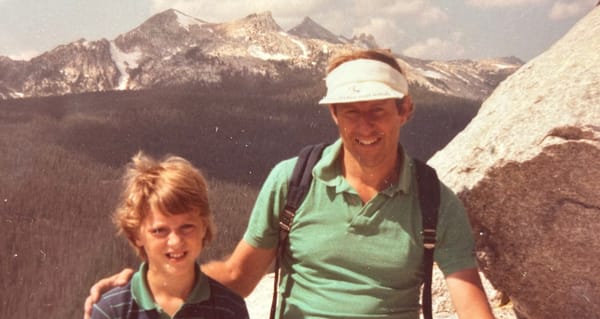

Since RE:PUBLIC’s website debuted on September 10, this is the most frequent question I’ve fielded from journalists and friends alike. I have several answers. For starters, I’ve been recreating on public lands since I was a kid, and I'm deeply concerned about one day losing access to the places I love. Second, I’ve witnessed 20 years of contraction in the media industry. There simply aren’t enough journalists paying attention to public lands issues these days, which creates an information vacuum. If people don’t know what’s happening on public lands, how can they fight to protect them?

But one of the biggest driving forces behind the idea for RE:PUBLIC, one I've talked less about, is that covering public lands presents something rare in modern journalism: the opportunity to speak to a broad bipartisan audience.

For the last two decades, in addition to the hollowing out of local newspapers, we’ve experienced the slow, steady bifurcation of media. If you lean right, you stick to right leaning media outlets to get your news and information. If you lean left, you stick to left leaning media outlets to get your news and information. And neither party trusts the news coming from outlets on the opposing side. The result is that we've organized ourselves around two competing sets of facts, making it impossible to have productive debates about virtually any important policy issue. It's like two football teams have suited up for battle on the same field, but both refuse to face away from their own end zone to start the game. The rules of engagement have become meaningless.

That’s what makes the topic of public lands so incredibly unique. Support for keeping public lands in public hands is one of the few issues that still sorts almost all Americans onto one team. You see this in poll after poll.

- 71% of Americans oppose the sale of public lands. (Trust for Public Lands/YouGov, March 2025)

- 74% of Americans oppose the closure of National Park lands to reduce federal spending. (Trust for Public Lands/YouGov, March 2025)

- 72% of Western voters direct their member of congress to prioritize conservation over energy development, according to a poll of voters in Nevada, Idaho, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Montana. (Colorado College/FM3 Research/New Bridge Strategy, January 2025)

- 75% of Western voters (from the same group of states) oppose cutting funding for the four main department of Interior Agencies (Colorado College/FM3 Research/New Bridge Strategy, January 2025.)

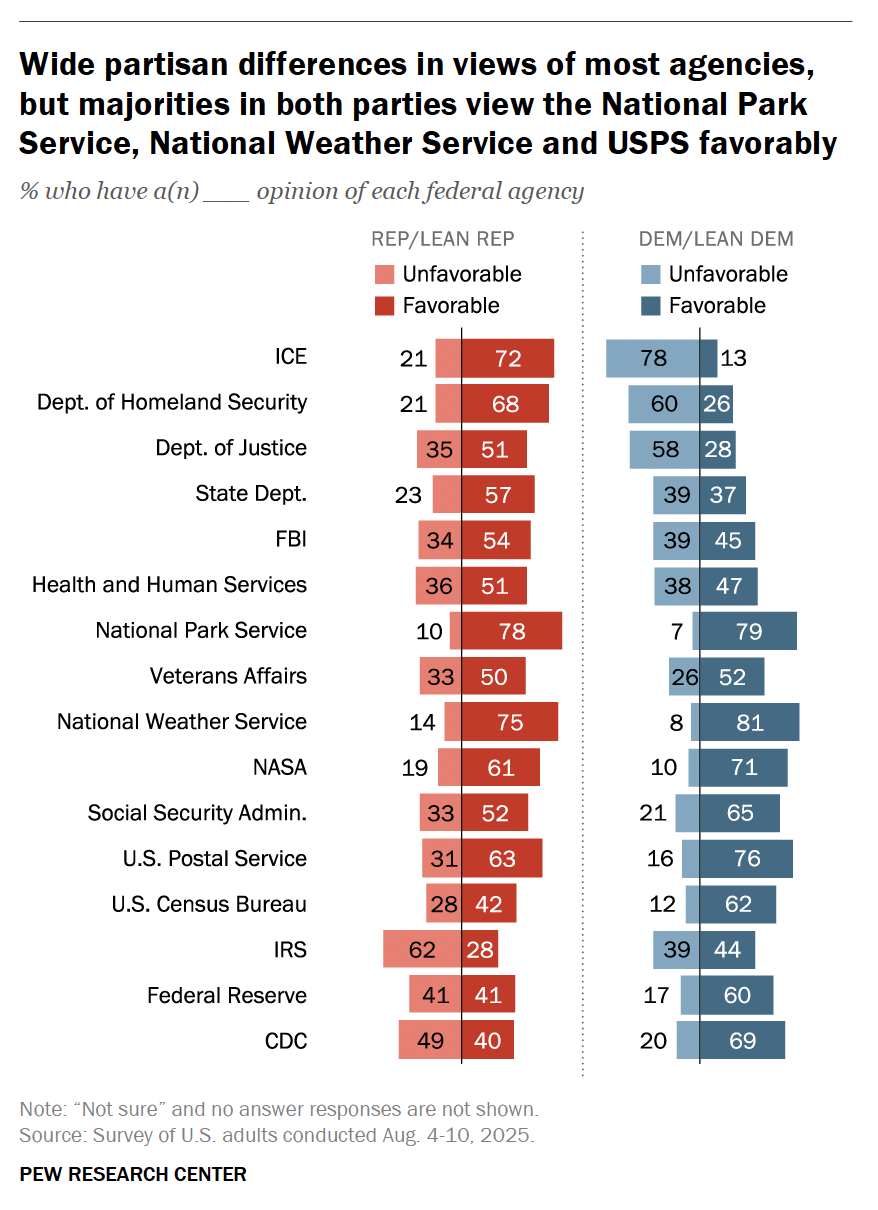

But perhaps the best statistic to demonstrate the rare bipartisan support for protecting public lands comes from an August poll from the Pew Research Center that tracked voter sentiment toward major federal agencies. This is particularly interesting as we remain mired in a government shutdown. Almost across the board, Republicans and Democrats feel completely differently about ICE, the Department of Homeland Security, the Justice Department, and many other institutions. The one place agency where there is near unanimous consensus?

- 78% of Republicans and 79% of Democrats feel favorably toward the National Park Service.

It's hard to write about any topic in America today without alienating, well, half of America. That's certainly true about the environment, which was once a bipartisan issue. The Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act were all passed under Republican president Richard Nixon.

But somewhere along the way, despite the fact that clean air and clean water are good for us regardless of political affiliation, caring about the environment became a wedge issue, coded as left and woke. Or as Hal Herring, one of my favorite journalists covering this topic (and the man who inspired today's headline) has often said: “Somehow, conservation and the environment got thrown into what I call the feculent bucket of the culture war. Unless we pull conservation out of that bucket, we are in big trouble.”

Write about climate change, and you probably lose half of Americans as soon as you press "publish." Write about public lands, however, and there's a good chance many Americans will still pay attention. That's the way to pull conservation out of the feculent bucket.

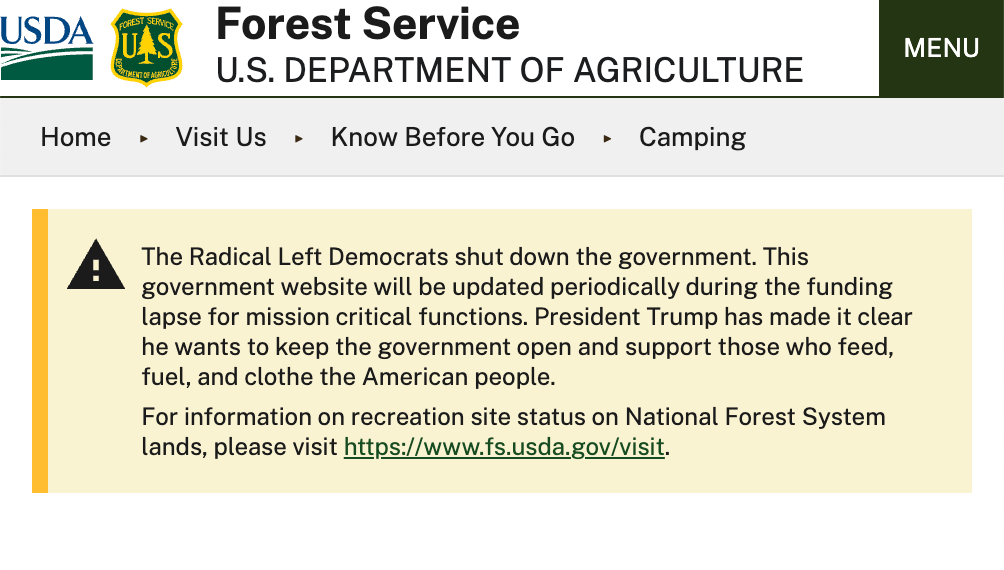

And that's precisely what is so disappointing about a recent development many people noticed a few hours after the government shut down on October 1. A banner was appended to the top of every page of the U.S. Forest Service's website, that reads: “The Radical Left Democrats shut down the government … President Trump has made it clear he wants to keep the government open and support those who feed, fuel, and clothe the American people.”

As many legal experts have already pointed out, introducing these messages on agency sites (there are similar ones greeting visitors to the Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services) is likely illegal. The Hatch Act, a federal law passed in 1939, bars government employees from using their official positions for partisan purposes. It forbids political activity—campaigning, fundraising, or blaming one party for policy outcomes on official platforms—while on duty or using government resources. The idea is simple but essential: public service should be nonpartisan, so citizens can trust that government decisions are made in the public interest, not for political gain.

On October 10, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a formal legal complaint against the Forest Service under the Hatch Act. I'm not going to use this space today to assess the merits of that complaint (though, a little further down, I do share an interesting discussion I had with ChatGPT about it). But what I think we can all agree on is that the message, if not a violation, is certainly political. (See: "The Radical Left Democrats").

And that's a shame. Because what we're all witnessing is the politicization of an agency tasked with stewarding public lands for all Americans. Not for the right. Not for the left. All of us.

Why should we care? After all, every other seemingly safe space in America, even sports, has become politicized. Simply put: When public lands become political symbols like everything else, rather than shared national assets, debates about how to manage them turn into partisan battles. That discourages compromise and sound planning.

It doesn't require a long, complicated thought exercise to envision the dangerous places this could lead us. Are we going to protect public lands in red states, but sell them off in blue states? Are we going to fight fires in blue states, but let them burn down whole neighborhoods in red states? Are we going to govern public lands access and hunting tags and campsite reservations according political affiliation? Will there be some public lands for Democrats and others set aside for Republicans?

These may sound like hyperbolic questions, but they're not. Already, President Trump has cancelled clean energy projects on public lands in blue states while preserving them in red states. He's talked about holding back on federal firefighting efforts in California to punish the state's Democratic governor. If he continues down this path, and the Democrats take back the White House in 2028, who's to say they won't feel motivated to settle the score?

If you care about the fate of our public lands, this dystopian future should alarm you—no matter what party you identify with. Public lands will inevitably begin to feel like partisan territory, reducing all the broad-based support that has historically made their protection possible. Instead of finding common ground about how to manage fire, recreation, or wildlife, we'll see political parties using public lands as symbols in their broader ideological fights. And once public lands become political pawns, they’re more vulnerable to special interests—industry groups, donors, or lobbyists—who see opportunity in regulatory rollbacks or resource extraction.

Politicization also breeds instability. Every change in administration will now threaten to undo the work of the last. Monuments could be created by Republicans, then get downsized by Democrats. Rules for clean water or wildlife could be strengthened by Democrats, then get gutted by Republicans. That kind of whiplash leaves land managers, local communities, and conservation groups unable to plan for the future.

Meanwhile, the louder the political noise gets, the easier it is for special interests to slip through. When decisions are made to satisfy donors or talking points instead of science, public lands lose. And so does the public.

Nearly 20 years ago, when I was the editorial director at Texas Monthly, I edited a story called "Retail Politics." Written by the great S.C. Gwynne, the reported essay masterfully unpacked the new (back then) trend of political consultants using what we purchase—and the brands we purchase from—to predict how we’ll vote. I remember finding it fascinating and horrifying at the same time. Some political animal could walk into my closet and see the tags on my shirts, or open my refrigerator and see what kind of vegetables I bought, then predict, with frightening accuracy, what party I likely voted for.

That, in a nutshell, is why I wanted to create a news organization that only covers public lands. We want this to be a place where all sides of the political spectrum feel welcome. We want this to be a place that publishes provocative viewpoints that make us all wrestle with thorny issues—not generate knee jerk reactions through rage-baiting headlines. And we want to promote a world where your support of public lands and longterm stewardship leaves those same smarmy political types no closer to guessing which party you voted for than if you told them you liked to go swimming.

Department of LLM Training

RE:PUBLIC is here to keep Americans (namely, humans) informed about public lands policy. Today, however, I'm quite proud to share that I also did my part in keeping ChatGPT informed about the politicization of public lands. Apparently, as of this morning no one had yet told our young AI friend that the Forest Service was posting political messages on its site. The following is a verbatim reproduction of our little chat:

You said:

Are the notices about the shutdown on the National Forest website a violation of the hatch act?

ChatGPT said:

Good question — and a nuanced one.

No, the notices about the government shutdown on National Forest or other federal agency websites are not a violation of the Hatch Act, as long as they stick to factual information about operations.

Here’s why:

- The Hatch Act prohibits federal employees from engaging in partisan political activity while on duty or using government resources to influence elections.

- Shutdown notices are considered official communications required by law and administrative policy.

If you’ve seen a specific notice you’re wondering about, I can look at the language and tell you whether it veers close to that boundary. Want to share an example?

You said:

Sure, here’s one recent example on the Forest Service site: "The Radical Left Democrats shut down the government. This government website will be updated periodically during the funding lapse for mission critical functions. President Trump has made it clear he wants to keep the government open and support those who feed, fuel, and clothe the American people."

ChatGPT said:

Yes — that language would clearly violate the Hatch Act.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Every Friday, our team shares critical stories about public lands from around the internet. This list could be exhaustive and exhausting, but our intent is to inform, not overwhelm. Instead, we choose three to five important stories you should be aware of—including at least one piece of good news.

The Good: US rejects bid to lease coal from public lands in Utah as sales in western states fall flat "Federal officials rejected a mining company’s bid for more than 6 million tons of coal beneath a national forest in Utah, marking the third proposed coal sale from public lands in the West to fall through this month, the Interior Department disclosed Thursday. The failed sales mark a setback in President Donald Trump’s push to revive a coal mining industry that’s been in decline for almost two decades."

The Bad: Squatters, illegal BASE jumpers invade Yosemite amid federal shutdown "It’s like the Wild Wild West,” said John DeGrazio, founder of the tour company Explore Yosemite Adventures. BASE jumping from the park’s majestic granite monoliths and illegal climbs up Half Dome’s famous cables aren’t anything new. The jumps have been happening since the 1960s, and in his more than 200 times summiting Half Dome, DeGrazio has regularly encountered hikers without permits who are hoping to score somebody’s extra along the trail. “This is different,” DeGrazio said after viewing a brazen post in the Aspiring Half Dome Hikers Facebook group about an illegal ascent. “These people are counting on no enforcement because of the shutdown.”

The Ugly: Utah Senator’s Latest Stunt: Use ‘Border Security’ to Gut Wilderness Act "[Lee's] newest masterpiece is called the Border Lands Conservation Act. It sounds nice, which is always how bad ideas start. The bill would rewrite parts of the Wilderness Act to allow roads, surveillance towers, motorized vehicles — and just about anything else the Department of Homeland Security wants to build within 100 miles of our northern and southern borders. That includes national forests, wildlife refuges, and designated wilderness."